It’s hard to summarize an origin country like Brazil and its vast role in coffee’s past, present, and future. Since the 1800s, Brazilian coffee has dominated the coffee trade. Brazil has been a top producer of Arabica and Robusta with an immense range of flavor profiles and processing methods. And every harvest, we bring coffee roasters fully traceable unroasted Brazilian green coffee beans that showcase the outstanding qualities of Brazil.

Coffee farmer in Brazil walking through coffee fields

History of Brazilian Coffee

The Brazilian coffee trade dates back to 1727 when Arabica seeds were imported (read: smuggled) into the country via French Guiana. In just a century, Brazil grew into the largest coffee producer in the world, and coffee dominated the country’s agricultural exports.

In the café com leite (coffee with milk) period of the 1880s, coffee boomed in São Paulo while dairy reigned in Minas Gerais. The agrarian oligarchs controlling the estates held most of the political power and instituted laws that streamlined production and export.

Slavery was abolished in Brazil in 1888, and the shift led to large movements of immigrants and laborers to coffee-growing areas. With the ample availability of labor, Brazil’s coffee output soared to 80% of the global supply by the 1920s.

Since then, other producing countries have ramped up their own exports, reducing Brazil’s overall market share. However, there’s still a 1-in-3 chance the coffee in your cup is from Brazil. Over 33 percent of the world’s coffee supply still comes out of Brazil — and that doesn’t include the coffee they keep to drink themselves.

Coffee is important to people in Brazil at every touchpoint of the supply chain, from growing to drinking, and the country consumes a little over 20 million bags domestically. They tend to keep back the beans that don’t meet export quality standards, though, making darker roasts with lots of added sugar the more popular way to drink local coffee. Here, the coffee supply chain generates over 8 million jobs for around 4% of the population. Today, there are nearly 8 million coffee trees in Brazil, a number that continues to grow each year.

Frost-damaged coffee trees in Minas Gerais

In 2021/2022, production took a dip due to the combined factors of an off-cycle year, adverse weather patterns, container shortages, and inflation. Although Brazil is still facing production challenges like high costs, steadily high coffee prices are helping to offset the impact. Meanwhile, coffee trees are making progress back to reaching full production potential. The USDA forecasts Brazil’s coffee exports to grow 26% to 45.35 million bags. Arabica production is expected to reach 44.7 million bags, 12% growth from the previous season. Robusta production is expected to fall 5% to 21.7 million bags due to factors stemming from adverse weather conditions in Espirito Santo.

Coffee Production in Brazil

Brazil’s traditionally moderate temperatures, heavy rainfall, and distinct dry season are all advantages when it comes to growing coffee. As a result, flowers tend to bloom uniformly, and cherries mature all at once. To manage this short harvest period, most Brazilian growers have mastered the use of machinery to make the most of the season.

Mechanical coffee cherry picking in Brazil

It’s a common misconception that machine-harvest coffee is of lower quality than hand-picked cherries. Machine harvest is no less meticulous, and a separate machine carefully sorts ripe, unripe, and overripe cherries before being further processed. This is preferable to cherries falling to the ground because they couldn’t be picked in time. With a production scale like Brazil’s, there just isn’t enough time to have individual pickers only going for the ripe cherries day after day.

While experienced farmers may be reluctant to embrace change, they can be very proactive about experimenting with the latest trends if they see a market opportunity. Brazil green coffee is traditionally natural processed, washed processed or pulp natural processed.

Coffee harvesting in Cerrado. Density sorters are later used to separate under-ripe cherry from ripe and dried cherries.

The recent trends in fermentation and anaerobic processes have also reached the Brazil. The farmers are actively testing these new processes and are eager to deliver creative coffee offerings to interested buyers. Fazenda Bela Vista is one such farm that experiments in growing exotic varieties and applying multiple processing methods, including a static dried process where cherries slowly dry in boxes that alternate heat and cold air for slow dehydration, resulting in a bloom in fruity and winey notes.

Overall, coffee farmers in Brazil are heavily invested in improving quality and adding value to their products as much as they can. Many are replacing chemical pesticides with biological inputs instead, with some using up to 50% fewer chemicals to reduce their environmental footprints while boosting economic gains.

A significant trend to note is increased attention toward specialty Robusta production. Marcelo Pedroza, head of Genuine Origin’s Volcafe Way program in Brazil, chalks it up to reactions to the current C-market as roasters consider high-quality Robusta as an alternative to Arabica. “The mother of innovation is need. If there’s a demand, farmers here will respond quickly. They are quite dynamic,” he says.

The total acreage of coffee farms in Brazil continues to grow, with the new addition of around 300,000 hectares that have recently come into production, for a total of 2.495 million hectares country-wide. Brazil is a one-stop shop for every kind of coffee there is, ranging from commercial grade Robusta to high-end specialty beans, with a wide variety of processing treatments. There are farms of all sizes, though the majority are considered small growers with areas of less than 20 hectares.

Due to Brazil’s massive market share in coffee exports, any disruption to its coffee production could have a major impact. A shock to Brazil’s coffee supply will ripple through the globe and could dramatically affect price. Climate change, with the threat of more drought and frost in particular, is a big concern for coffee. Changes to farming practices like increased reliance on irrigation may be in the cards for the harvests to come.

Coffee varieties in Cerrado de Minas, Brazil.

Common Brazilian Coffee Varietals

The most common Arabica varietals found in Brazil are Bourbon, Caturra, Catuaí, Mundo Novo, and Acaiá. Sub-varietals include Yellow and Red Bourbon, as well as Yellow and Red Catuaí. Maragogipe is another notable varietal from Brazil discovered in Bahia in 1870, but its low productivity led to a decline in popularity throughout the industry.

The first coffee variety planted in Brazil was Typica, and many subsequent cultivars are based on Typica’s genetic foundation. The genetics department of the IAC was launched in 1928 and went on to develop many new coffee cultivars. After coffee leaf rust spread across the country in the 1970s, the IAC released the Icatu varietal, developed from a Robusta and Arabica hybrid. Icatu’s high productivity and resistance to pests and diseases led to wide adoption throughout Brazil’s coffee farms.

Green coffee drying on patios in Brazil farm

Brazil’s Green Coffee Producing Regions

The biggest coffee-producing regions in Brazil are São Paulo, Minas Gerais, Bahia, Paraná, Espírito Santo, and Rondônia (of mostly Robusta).

Minas Gerais alone produces more coffee as a region than any other country in the world, at around 30 million 60-kg bags per year. The region accounts for nearly half of Brazil’s total production. Minas Gerais is often broken up into sub-regions, with some of the most renowned including:

- Sul de Minas (South of Minas), where the average temperature is 71ºF and altitudes range from 700 to 1,200masl. Farms here are on the small side, with properties that range from 10 to 100 hectares. In the cup, coffee from Sul de Minas is full-bodied with citric notes and fruity aromas.

- Cerrado de Minas is the only region with Designation of Origin status. Temperatures here range from 65 to 73ºF and an altitude of 800 to 1,300masl. Medium- to large-sized farms are located throughout 55 municipalities, some with a few hundred acres all the way to large estates. The cup profile of Cerrado green coffee offers a medium body with high sweetness and acidity.

- Chapada de Minas is home to around 6,000 producers spread across 30,000 hectares of coffee farmland at 1,000 to 1,500masl. The temperature runs from 68 to 75ºF, and coffee from Chapada de Minas offers a cup profile of sweet, chocolaty, and caramel characteristics with intense aromas.

- Matas de Minas is a warm and humid sub-region of Minas Gerais with large variations in elevations ranging from 600 to 1,4500masl. Most farms are modest by Brazil standards, with 80% smaller than 20 hectares. Mata de Minas is sweet in the cup, with citrus, caramel, or chocolate notes.

Brazilian Coffee fields in Minas Gerais

São Paulo is where the Port of Santos, Brazil’s main export channel, is located. There are two main sub-regions here, Mogiana and Centro-Oeste São Paulo. The average temperature runs at a comfortable 68ºF, and favorable altitudes of 900 to 1,100masl make for a very sweet and balanced cup profile.

Espírito Santo is the second-largest coffee-producing state, but mostly of commodity-grade Robusta. Sub-regions include Montanhas do Espírito Santo’s highlands, which produce some specialty-grade coffee, and Conilon Capixaba, with altitudes ranging from 700 to 1,000masl. Unlike in the rest of Brazil, the coffee here is processed with the washed or semi-washed method because the climate and high altitude make Espírito Santo’s environment mistier and more humid.

Bahia is a newer region to the coffee scene. Cultivation began in the 1970s, and the region quickly gained traction as a producer of high-quality coffee using innovative technology. The Cerrado and Planalto da Bahia sub-regions are the most high-tech in Brazil, with full mechanization at every stage, from cropping to irrigation to harvest. High altitudes, warm temperatures, and maximized efficiency result in the highest productivity rates in Brazil.

Paraná is the southernmost coffee region in the world. Although the altitude doesn’t exceed 950masl, you can still find sweet coffees with bright acidity and complex flavors in this region. The climate is a little cooler, but that doesn’t stop Paraná from producing 25% of Brazil’s agricultural products, including wheat, corn, soy, tomatoes, sugar cane, and coffee.

Rondônia specializes in growing conilon, a Brazilian Robusta. The climate is defined as tropical, with high temperatures and low altitudes nestled in the Amazon rainforest.

Brazilian Green Coffee Quality

Brazil was the first to establish a formal grading system for classifying coffee beans. In 1836, a law that categorized coffee according to the number of green bean defects in the lot came into effect. This approach to grading coffee is still used around the world today. However, it wasn’t until 1910 that a sensory quality component was added to the grading system.

In 2002, the Brazilian Official Classification (Classificação Oficial Brasileira, or COB) was standardized by the Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture (MAPA), and they outlined precise protocols for cupping and grading green coffee.

Today, you’ll often find lots of Brazil green coffee marked with a NY 2/3 grade referencing the Green Coffee Association of New York. This standard signifies that no more than 8-12 visible defects are present in a 300-gram sample of coffee. Another classification for coffee from Brazil is screen size, meaning that the coffee beans have been sifted through standardized screens such as 17/18 or 15/16 and sorted by average bean size. Larger bean sizes are often associated with higher quality.

Other designations include abbreviations like SSFC (Strictly Soft Fine Cup) or MTGB (Medium to Good Bean Size) that originate from the original COB grades outlined below, from higher to lower quality:

- Estritamente Mole (Strictly Soft), around 85+

- Mole (Soft), around 80-84

- Apenas Mole (Just Soft), around 75-79

- Duro (Hard), around 68-74

- Riado, below 67

Barista brewing pourover coffee | Img Andreantian

What does coffee from Brazil taste like?

Roasted coffee from Brazil is often a pantry staple due to its reliable profile of rich, full-bodied flavor and low acidity. However, the sheer size of the country and its diverse microclimates beget an expansive range of cup character that goes far beyond that.

For example, coffees from the Minas Gerais region often have a smoother and more balanced flavor with notes of milk chocolate and nuts. On the other hand, coffees from the Cerrado region may have fruitier undertones.

Overall, Brazilian coffee provides a satisfying and flavorful cup that appeals to a wide range of coffee enthusiasts. In addition, its versatility and consistent quality have made it a popular choice for both espresso blends and single-origin coffees.

Genuine Origin in Brazil

Volcafe Brazil, Genuine Origin’s sister company and sourcing partner, has a presence throughout the coffee states. Founded in 1954, Volcafe Brazil is one of the top five coffee merchants and exports over 1 million bags of coffee internationally while also distributing over 1 million more bags domestically. The company is ahead of the curve when it comes to sourcing coffee from responsible programs, with 25% of exports coming from certified labels in contrast to the country’s overall 17% certified coffees.

The sheer size of Brazil adds complexity to coffee logistics. For a green coffee supplier like Volcafe Brazil to move coffee across the different states and to the export ports, they need to understand each state’s tax requirements and laws thoroughly. Their huge warehouses, located throughout the coffee regions, can hold up to 590,000 bags in a certified and carefully regulated storage facility. Around 80% of the country’s coffee goes out through Santos in São Paulo, where Volcafe Brazil’s head office is established.

For Volcafe Brazil, the most important thing is that they do what they do with passion and do it properly. Since 2015, they have been ramping up their practices in coffee purchasing and training with the Volcafe Way, strengthening their relationships with producers through knowledge-sharing and technical support to achieve sustainable profitability.

“The field team is growing every year as we advance our responsible sourcing program,” says Marcelo, head of our Brazilian specialty coffee division. “We’re getting to know the supply chain in preparation for future demand and doing our due diligence by supporting farmers and engaging in new implementations of the [Volcafe Way] program on the ground.

The three main pillars of their work include:

- Increasing productivity through more efficient resource consumption.

- Improving the production of high-quality coffee.

- Supporting farmers to become more profitable.

Volcafe Brazil technicians visit one or more farms every day, reaching nearly 600 farms across 67,000 hectares.

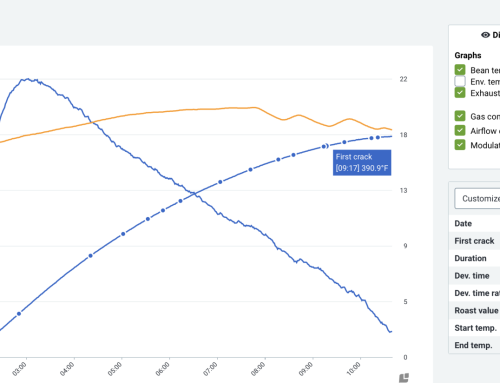

New processing methods definitely contribute surprising flavors to the coffee cup, and these surprises keep things fresh for the Volcafe Brazil quality control team. The team is constantly cupping — sometimes up to 500 cups in a single day. Every bag of coffee is cupped again and again, from farm gate to buying house to head office in Santos, before it leaves the country.

The quality control team, which includes five Q-graders, purchasing specialists, and roasting assistants, also works closely with customers to develop custom specialty coffee blends. One of the blends to come out of Volcafe Brazil’s research and development is the highly popular Salmo Plus Natural, which tastes like a deliciously nutty baked treat with hints of cocoa powder and orange zest.

We’re looking forward to expanding our Brazil microlot green coffee and organic Brazil green coffee offerings in the future, as well as increasing our range of unroasted green coffee from Brazil on both sides of the spectrum – from entry-level price points to high-scoring micro-lots. Roasters can look forward to Mata de Minas Pulped Natural, a new green unroasted brazil pulp natural coffee, single-variety brazil yellow bourbon green coffee beans

Find more about our Brazil green coffee collection at Genuine Origin’s Brazil portfolio on our website: https://www.genuineorigin.com/brazil